When fantasy left the forest...so did we.

|

| 'Inviting forest' by perodog @ dA |

Looking at the connection between nature and happiness, and the books that get us outside...

One of the most poignant discussions for me in Gossip from the Forest was about the amount of time children are spending outdoors:

We are doing something very alarming to our children - and, making it worse perhaps, we have fooled ourselves that we are doing it for their sake, for their safety. The amount of unsupervised time outside the home that young people get to enjoy is being reduced year on year (the average child has lost a whole hour a day already this century). (1)In 2007 Unicef published a report that stated children in the UK are the unhappiest of all the economically developed countries. Despite children themselves stating that 'having plenty to do outdoors' would make them happy, their parents felt under pressure to buy them the latest gadgets and gizmos instead (read The Guardian article on this here). The lack of connection to nature, or 'Nature Deficit Disorder', has made our country miserable. This worried David Bond so much that he set up Project Wild Thing and gave himself the title of Nature's Marketing Director, thinking that Nature needed a helping hand in getting children back outside. He created the Wild Time App, featuring a wide range of nature based activities that can be done in the time you have available, whether it's 10 minutes or 2 hours. The National Trust has also provided a list of 50 things to do before you're 11 3/4.

|

| 'Exploration' by perodog @ dA |

Interestingly, we have also abandoned another genre of literature, one which encouraged children to see themselves as capable on their own in the wild. There is a sort of novel for younger readers that was immensely popular up until the last quarter of the twentieth century and that has now well-nigh disappeared: stories of adventures in which children are on their own and deal with problems under a veneer of realism; novels like Swallows and Amazons or The Famous Five... (2)Looking at the shelves in bookshops I would not have imagined this myself; Enid Blyton seems to be a pretty permanent fixture at least. In 2010 The Famous Five publisher tried to boost sales of the series by modernising the language, although they claimed their sales weren't suffering before they took this action. Perhaps this is the problem, then: relevance to the modern world. Maybe the child is too harsh a critic to really believe it possible that parents would let their children go off alone on camping trips like Julian, Dick, George and Anne do. Suspending disbelief to make this seem credible would then make the book a fantasy tale rather than an adventure story...would it not?

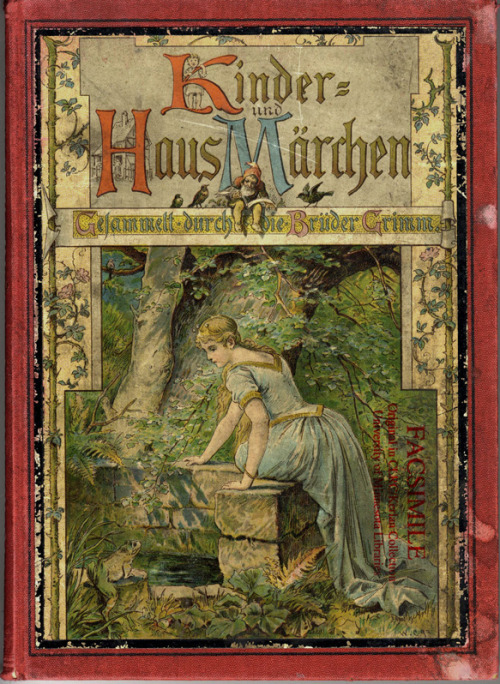

We have kept the magical element of fairy stories in modern books for young people; fantasy worlds are now the location of adventures and moral combat. But we have abandoned the immensely reassuring realist element of these old tales: the forests are dangerous but you can survive; use your own intelligence and courage and you will come back safely. (3)The wonderful thing that fairy stories create is this idea in the back of the mind that when you walk through a forest, something magical might happen to you. There are few other stories I can recall from my childhood that give me this sensation when I walk in the woods, or indeed in any other natural place.

So, do we need to bring the magic back home? Is this the challenge of the modern writer, who cares about magic, who cares about nature, and who cares about the wellbeing of children? A quick browse of the list of current children's bestsellers and upcoming releases tells me that most of the stories are fantasies or mysteries set in the city (often with supernatural creatures prowling the streets at night). I'm not surprised. Ten years ago when I was a teen, finding a new book set in the countryside felt like a rarity even then. Maybe this can be my challenge as a writer. And a challenge as a reader, to find these rare jewels - any suggestions would be most welcome, please share them with me in the comments!

|

| 'A tree of a salamander2' by perodog @ dA |

Woods between Worlds

(1) Maitland, Sara, Gossip from the Forest, (London: Granta, 2012), 98.

(2) Ibid., 104.

(3) Ibid., 105.

(1) Maitland, Sara, Gossip from the Forest, (London: Granta, 2012), 98.

(2) Ibid., 104.

(3) Ibid., 105.